Bridgewater Associates: 3 Ways to Protect Your Portfolio from Inflation in 2022

Key takeaways:

Zero interest rates mean you have a 3-to-1 loss-to-gain proportionality on nominal bonds.

Bonds no longer work as a diversifier in your portfolio to offset equity moves.

Inflation sensitive assets, equities with stable cash flows and geographic diversification are three possible ways to engineer the portfolio for the next decade.

I. The Impact

Every investor should know the importance of the interest rate. After all, it is the price of credit and the discount rate on all other cash flows.

And as Bridgewater Associates – the world’s largest and most successful hedge fund of all time – recently noted, the zero interest rates environment coupled with high policy-induced liquidity are the most important factors to take into account when structuring an investor’s portfolio going forward.

Bridgewater claims that assets in the economy are going to behave very differently in this new climate.

And plenty of others are validating this thesis by estimating that the plain vanilla 60/40 portfolio is likely to deliver paltry returns over the next decade. As a matter of fact, AQR Capital Management recently calculated that the return now sits at 2% after inflation.

So investors need to have a game plan for dealing with these new realities.

Let’s start with explaining the impact of zero interest rates as they influence:

1. Bonds and their returns:

Bonds – as an asset class – now return close to zero but, in addition, the return has an asymmetric payout pattern. If you would allow bonds to go from where they are now to zero, you would make 7% in the next three years. But if the real yield drifted up to its normal level, you would lose about 20%. This means you have a 3-to-1 loss-to-gain proportionality when contemplating an investment in nominal bonds.

2. Other assets vis-à-vis the discount rate effect:

Equities benefited from the lower discount rate on future profits resulting from lower rates. However, now you lose the ability for the discount rate to fall to cushion the potential decline in the cash flows of those assets when there is an economic downturn.

For the past 40 years, the decline in bond yields from 15% to zero has been a great tailwind for assets. You simply don’t have that going forward.

3. Portfolios with respect to correlation, diversification and balance:

In the past, the discount rate could fall and bonds could rally during periods of adverse economic conditions. So bonds have been a great diversifier during times of an economic downturn. They served an incredibly important purpose in portfolios in terms of balancing equity moves.

Some of the best bond rallies ever were from 3% all the way down to the current levels. When you have a 3% bond yield and a 0% short rate, you have a very steep yield curve slope and you can make a lot of money on bonds relative to cash.

However, now we have gotten to a point where the yield curve slope is flat. This means that people can start moving on to storing cash and doing other things, if the bond yield becomes too penalizing.

It is, therefore, time to have a conversation about alternatives.

4. Economies:

The last thing is the impact on economies. Historically, when there was an economic downturn, the ability to cut interest rates could stimulate the credit expansion. Now, as you can’t cut interest rates, the capacity to create a boom is substantially diminished.

II. What To Do

So in light of all of these tendencies, how should you restructure your portfolio?

As Bridgewater points out, you need to have a strategy. To either get out of all your bonds now or to get out of them as they come down to even lower levels.

The illustrious hedge fund claims there are three practical steps you can take:

1. Shift from nominal bonds to inflation-sensitive assets

First of all, you have to visualize what is going to happen in the next economic slowdown. What are the available policy responses? What assets will do well, if equities don’t?

Bridgewater’s basic view is that we’re now in a Monetary Policy 3 or MP3 world (i.e. a lot of money printing and fiscal spending). When there’s a slowdown, the government response is somewhat predictable. There will be more money printing and more fiscal spending.

But what assets will that money flow into, if it does not flow into equities?

When Bridgewater looked at the history of periods of big money printing and fiscal expansion, they found that assets such as gold and inflation-indexed bonds can create that balance. These are the liquid instruments that they use.

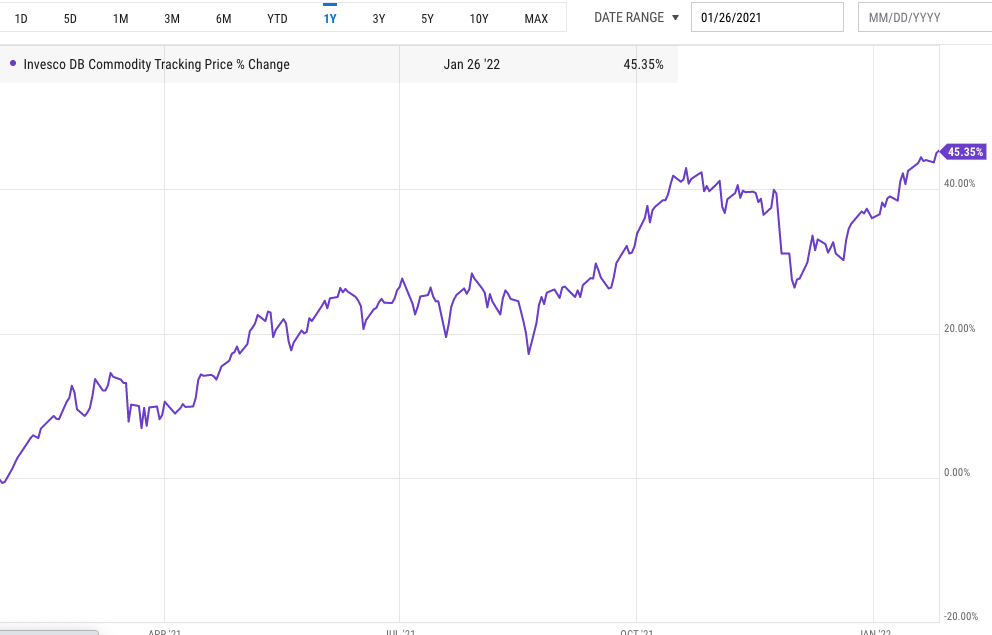

Broad, diversified baskets of commodities also make a whole lot of sense.

It’s important to note that there weren’t many environments like the one we are in. So Bridgewater uses the 1940s as the best example, when there were huge moves in real yields up and down, while nominal yields were pegged.

However, it’s important to remember that all asset classes are reflecting low likely returns over a very long period of time.

Additionally Bridgewater stresses that:

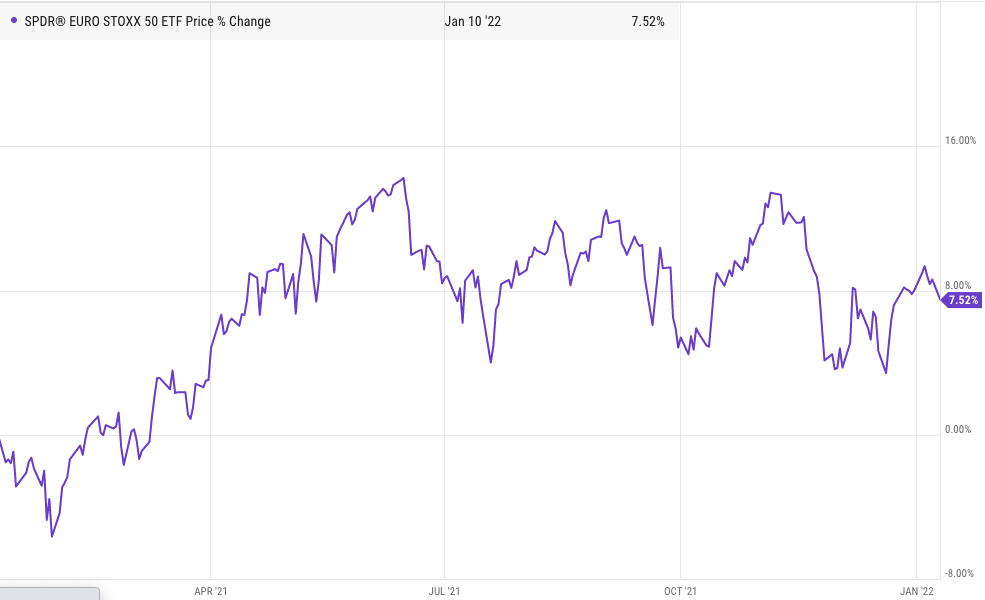

(1) in the short term, there could be big moves in these markets, as few people have protection in this environment. So there will be a continued adjustment in those assets, as people try to get the necessary protection (please see the three charts below); and

(2) it is important to recognize the difference between nominal and real returns. While you can get high nominal returns, it doesn’t mean there will be high real returns.

You also have to think of a balance between deflation and reflation. Both are risks that exist. And the purpose of finding the right balance in a portfolio is to try and mitigate both of them as much as possible.

This is why Bridgewater thinks that the move to inflationary assets is very beneficial, as it doesn’t cost you much in terms of increased risk of deflation.

In particular gold is not an inflation asset only. It is also a monetary stability asset. When Bridgewater looked at all the painful deflations in the past, gold created some balance in unstable deflationary depressions.

Of course, there is also a risk of having deflation with favourable economic conditions. This would mean that equities would do well but your inflation-linked bonds would get hurt.

However, you rarely see extended deflations when policymakers have fiscal policy and their own currency to print. Reflations are typically successful against deflations, unless they’re stuck in a gold or currency peg.

Until recently, the central banks were reflating (i.e. expanding output, stimulating spending and curbing the effects of deflation). So the policy response was in the other direction, where policymakers were trying to make cash and nominal bonds a very bad thing to hold.

And they were successful.

As Bob Prince, Bridgewater’s Co-CiO recently noted “if you are a holder of T-bills or cash of some sort, we’ve already had a 15% decline in your real purchasing power and counting. Another 10 years and it’s going to be 35%”.

He added that “cash is one of the riskiest assets you could hold through environments like this. Cash and bonds are among the most expensive assets in the world and they are destroying wealth through negative real returns”.

This is why Ray Dalio, Bridgewater’s Founder continuously claims that “cash it trash”.

And now we can actually see the effects of MP3 play out in front of our eyes.

As a result of coordinated monetary and fiscal policy, excess liquidity flowed into people’s pockets and drove asset prices up.

Then a self-reinforcing cycle kicked in:

the government gave money to people through the fiscal pipe;

this shot of cash raised people’s incomes (but not their productivity);

the beneficiaries then took some of that money and spent it;

this spending went straight into raising other people’s income who spent it too;

before long, this continuous whirlwind of high nominal spending and income growth became self-sustained, outpaced supply and produced inflation.

So, in the grand, archetypical scheme of things, Bridgewater is placing our predicament here:

What typically follows is that:

tightening causes discount rates to rise;

more aggressive tightening causes assets to fall; which then causes

a credit contraction, downturn in growth and downward pressure on inflation.

Now, with CPI hitting 7%, and the Fed’s behind-the-curve hawkish pivot, taper is the only talk of the town.

Bridgewater claims that wages and housing will be sticky and inflation will be significantly above what is currently discounted:

So the question remains how much the Fed is going to tighten.

The hedge fund sees two possible outcomes here. We either get:

higher than expected inflation or

more than expected tightening.

And they are positioning for both.

2. Shift into equities with more stable cash flows

According to Bridgewater, the idea of shifting into equities with more stable cash flows and cash-flow-based investing more generally will be a very interesting area of thought and research going forward.

Bridgewater has been looking at the returns of an asset and splitting it into two parts:

(1) the cash flow part of the return; and

(2) the discount-rate part of the return.

And then explicitly recognizing the drivers of each one.

When you do that, it opens up a whole pathway for portfolio structuring which looks at the nature of the cash flows and what drives them.

From there, there are two paths you can follow.

One is to find assets that have cash flows that won’t have sensitivity to a decline in the economic environment.

Second is to identify assets that have exposure to the environment but are offsetting and balancing, so that you can balance one asset versus another and create a portfolio of assets whose cash flows are well-diversified.

Bridgewater looked back in history and found that you can create a much more diversified portfolio of cash flows than the correlation of returns. That’s because historically, the discount rate applies to everything uniformly. But as we go forward, the discount rate is not going to have as much of an effect.

You also need to recognize that going 5 or 10 years into the future, ultimately cash flows are the dominant force on returns anyway. (This is the most important sentence in this post). So as a long-term investor, you can think in terms of structuring portfolios that have generally reliably rising cash flows over time regardless of the economic environment.

In essence, you are looking for CFOs that paint such a picture:

This can be achieved through good diversification or because you have chosen a set of classes that can give you a reasonable expectation of a positive return over time with the discount rate affecting things in the short term but knowing that it will net out over time in a positive way.

One of the ways that Bridgewater has done that was to identify types of spending which are going to occur no matter what the economy does and across any country in the world.

By identifying these types of spending, you can neutralize what would normally be a decline in the cash flows that would have to be offset by the discount rate. This way you don’t have to experience those declining cash flows.

In light of the imminent tightening, there is one other variable you need to take into account and that is finding equities which are not sensitive to the pull back in liquidity:

3. Geographic diversification

Finally, Bridgewater asserts that geographic diversification will play a bigger role in portfolios than it has done in the past.

Bridgewater posits that being geographically diversified benefits the outcomes of the portfolio across all time. However, over the last 20 years, it hasn’t been a big deal because many assets have been highly correlated due to the free flow of capital, the globalization of trade and other trends.

Going forward, Bridgewater sees major differentials across countries, as the level of correlation is falling.

Bridgewater also observes that China is facing an opposite set of circumstances than the US and the EU:

China’s bond yields have room to fall, while bond yields in the US and Europe are rising.

China’s equity market is down, while Western stocks are elevated.

China is transitioning to moderate easing, as the developed world is bracing for the onslaught of QT.

Just have a look at the prefect inverse correlation:

So Bridgewater is now less bullish on assets versus cash across the developed world, while viewing Chinese assets as attractive.

And this is just a foretaste of the rapidly changing world order, as the machine of evolution takes us through the rise and fall of empires and we move from interdependence to independence.

Disclaimer/Disclosure: This is not investment advice. This post is for educational purposes only.